Among the great Native American warriors are Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and Geronimo, all of whom are associated with the United States’ western expansion and the resistance it provoked. These were figures of the Wild West and now part of America’s mythology.

But another great Native warrior, often overlooked, was a man of mixed heritage who lived, loved and fought in the Southeast, who was born in Alabama, forced to resettle in Florida, led a guerrilla war against a U.S. Army and eventually was imprisoned on Sullivan’s Island, where he died.

His name was Osceola.

Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island, includes the burial grounds of the legendary Seminole Indian.

Captured by trickery by a frustrated Army general bent on keeping him from continuing to resist resettlement in the West, Osceola was sent to die in a South Carolina prison.

Historian Mark Derr writes in Some Kind of Paradise that Osceola was shipped out of Florida to isolation at Fort Moultrie to keep him from having contact with other Seminoles still in Florida or Indians forced to the western territories.

In life, he was perhaps the most influential of the Seminole leaders. In death, he became a legend. Mysteries surrounding his burial grounds remain unsolved to this day.

As a child, Osceola, born to a Creek Indian named Polly Copinger, was named Billy Powell. Historians are not sure of his father’s identity but suggest that Osceola was not a full-blooded Indian.

Billy Powell adopted the name Osceola when he became a teen-aged warrior. He was captured briefly and released by Andrew Jackson in 1818 in North Florida, according to historian, Irvin Peithman’s The Unconquered Seminole Indians. He and his mother moved to an area near Silver Springs in 1830, close to Fort King.

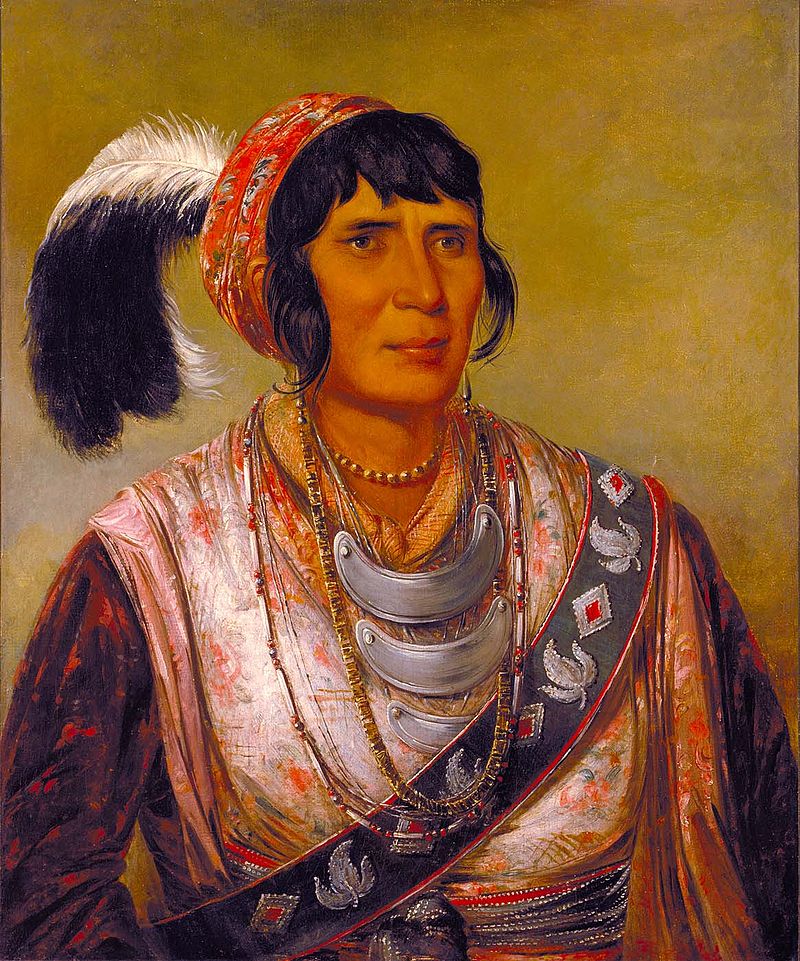

On the southern banks of Lake Monroe, toward the end of the Seminole wars, an Army officer painted Osceola’s portrait during one of many truce talks at Fort Mellon.

Osceola, a bigger-than-life hero of his times, refused to compromise with the Army. At Fort King, Osceola is said to have been asked to sign a treaty. He unsheathed his knife and pinned the document to a table.

Peithman writes that Osceola said, “The land is ours – this is the way I shall sign all such treaties.”

Osceola, other Seminole chiefs and escaped black slaves went on to wage a guerrilla war that frustrated the Army. By late 1837, though, Osceola’s health was failing. Suffering from chronic malaria and accepting that the Seminoles would be forced out of Florida, he met with soldiers under a cease-fire. Betrayed and captured, he wound up at Fort Moultrie, on Sullivan’s Island where he died.

His body was buried in Charleston, but the post surgeon decapitated the corpse and took the head to his St. Augustine home. Dr. Frederick Weedon displayed the skull to entertain his friends and intimidate his children.

The skull eventually ended up at the Surgical and Pathological Museum in New York, where it vanished during a fire in 1866.

But that is not the end of the legend.

The late Otis W. Shiver, a crusty Miami politician and an admirer of Osceola, claimed that in 1966 he drove to Fort Moultrie, dug up the Seminole’s grave and smuggled the bones back to Florida.

National Parks officials scoff at Shiver’s claims, saying he never dug deep enough to get anything and that because of the acidity of the damp soil, the bones would have long since decomposed.

For years, Shiver claimed he had the bones stashed in a Miami bank’s safety deposit box while he tried to find a suitable Florida site for a burial. His first choice was somewhere in the Ocala National Forest.

Did Shiver really have Osceola’s bones? He died in 1988, taking the answer with him.

For more information on Sullivan’s Island and its rich history, please contact THE BRENNAMAN GROUP: 843.345.6074